"Behind the Bands: Breeding Trials with the Tri-color Hognose"

Introduction

With its striking red, black, and white banding, the Tri-color Hognose (Xenodon pulcher) has become a coveted species in the reptile trade. Often mistaken for a morph of the Western Hognose (Heterodon nasicus), their bold appearance hides a more delicate reality: while these snakes can be prolific breeders, they are also notoriously prone to complications post-breeding—from feeding crashes and unexplained losses to high sensitivity to environmental stressors.

Like many keepers drawn in by their beauty, I underestimated the challenges involved. From inconsistent care guides and outright false information to puzzling reproductive behaviors, Xenodon pulcher has tested my patience, knowledge, and expectations at every turn. Success isn’t merely defined by producing eggs—it hinges on raising healthy hatchlings that thrive beyond the critical early months, and perhaps most challengingly, on ensuring that adult animals remain stable and in good condition after breeding, which in my experience has proven to be the most difficult aspect.

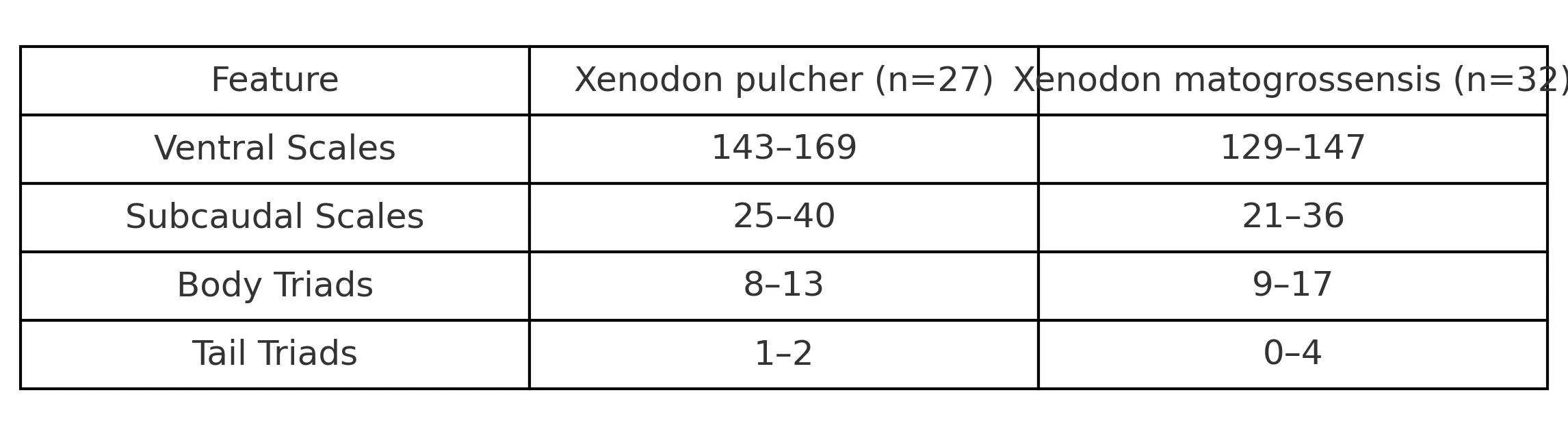

This species is often marketed as “beginner-friendly” by sellers eager to meet demand—a claim that holds some truth if the goal is simply to keep a single individual as a pet. However, achieving long-term success in breeding Xenodon pulcher is an entirely different challenge. It demands a nuanced understanding of their natural behaviors, seasonal cycles, and subtle physiological needs—areas I find myself continuing to learn more about with each breeding season. Many keepers, myself included, have discovered the hard way that conventional reptile breeding practices often fall short. To add to the complexity, a surprising number of keepers, again myself included, unknowingly work with hybrid individuals—crosses between different types of tri-color hognose—which can further complicate breeding outcomes and consistency. The two being Xenodon pulcher and Xenodon mattagrossensis. While Xenodon pulcher is widely recognized in the pet trade as the “Tri-color Hognose,” Xenodon mattogrossensis lacks an established common name. This lack of distinction has contributed to persistent confusion, with both species frequently mislabeled or collectively referred to as “Tri-color Hognose” despite their significant ecological and behavioral differences. Also, in the days when it was legal to import from their countries of origin, importers did not recognize the different species and sold them all as “Tri-Color Hognose”. The issue is further compounded by their similar external appearance, which can easily mislead even experienced keepers and breeders.

This article shares a candid look at my multi-season journey—highlighting what worked, what failed, and what I wish I’d known sooner. Whether you're an experienced breeder or a curious newcomer, I hope my experiences help shed light on the often glossed-over realities of working with this fascinating but frustrating species.

Challenges in Breeding and Maintaining Adult Females

Over the years, I’ve encountered a range of health complications while working with Xenodon pulcher—everything from egg binding and tooth impactions to mysterious “broken backs.” While these issues might seem like isolated incidents, I believe they reflect broader, underlying problems that emerge primarily during or after the breeding process. Interestingly, raising juveniles to adulthood has rarely posed significant challenges. The majority of complications I’ve experienced arise once females begin reproducing. In contrast, males have proven far more resilient; one of my males lived for over six years—relatively short by most standards, but nearly double the lifespan of several of my breeding females.

I don’t believe these outcomes are coincidental. Rather, I suspect a combination of factors are at play, including improper diet, inadequate hydration practices, and—perhaps most importantly—the unintentional hybridization of X. pulcher and X. mattogrossensis in captivity. Early in my experience, I unknowingly acquired what I now believe to be a different species than advertised. The physiological differences became apparent with time: X. pulcher tends to be longer and more slender, while X. mattogrossensis appears shorter and more robust. These distinctions also reflect deeper biological differences that influence reproductive success and survivability.

One particularly troubling issue is the sudden death of females following their first breeding season. In my experience, the most likely culprit is dehydration. Back in 2018, when I received my first trio of Tri-color Hognose from a breeder, he emphasized the importance of regular soaking. At the time, I didn’t fully understand the advice—I assumed that high humidity and access to a large water bowl would be sufficient. But after several breeding cycles, it became clear why soaking is so critical.

Unlike many other snakes, Tri-color Hognose do not actively seek out elevated water sources. If a water bowl is positioned even slightly above substrate level, a gravid female—especially one carrying large follicles—may avoid the extra exertion of climbing to reach it. This can lead to chronic dehydration, which I believe is a major contributing factor to the high post-breeding mortality in females. Yet lowering the bowl comes with its own challenges: substrate often contaminates the water, requiring constant maintenance. This can be fixed with regular soaking 3-4 times a week!

Morphological Comparison: Xenodon pulcher vs. Xenodon matogrossensis

Climate and Habitat: Understanding the Environmental Divide

A key factor in understanding the differences between Xenodon pulcher and Xenodon mattogrossensis lies in their distinct native climates. Though often confused in captivity, these two species are adapted to very different environmental conditions in the wild.

X. pulcher inhabits the Chaco ecoregion—an expansive dry zone stretching across eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, and northern Argentina. This region experiences a subtropical to semi-arid climate with dramatic seasonal shifts. Summers can be intensely hot, with temperatures reaching up to 120°F, while winter nights occasionally dip below 32°F. Annual rainfall ranges from approximately 18 to 55 inches, concentrated mostly during the warmer months, though high evaporation rates often offset the available moisture. The landscape varies from dense thorn scrub to dry forest, depending on elevation and precipitation patterns.

In contrast, X. mattogrossensis is found in Brazil’s Pantanal floodplain, covering the states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul—one of the largest tropical wetlands on the planet. This area is characterized by a tropical wet-and-dry climate, with average yearly temperatures between 73–77°F and annual rainfall totaling around 39 to 75 inches. The wet season, from October through March, brings heavy rains and extensive flooding, transforming much of the region into shallow aquatic habitats. During the dry season (April to September), waters recede to reveal grasslands, forest patches, and savanna. These seasonal extremes play a crucial role in shaping the ecological rhythms and physiological adaptations of the species found there.

Understanding these climatic differences is essential for anyone attempting to keep or breed either species in captivity. Environmental mismatches—particularly in humidity, temperature cycling, and seasonal cues—can contribute to stress, failed reproduction, or chronic health problems in both species.

Geographical Differences Between Xenodon pulcher and Xenodon mattogrossensis

Xenodon pulcher is primarily associated with the Chaco ecoregion, and its range includes:

Eastern Bolivia

Western Paraguay

Northern Argentina

Now confirmed in southwestern Brazil (Porto Murtinho, Mato Grosso do Sul), marking the first verified Brazilian record and extending its known range 100 miles east of previous localities in Paraguay.

Xenodon mattogrossensis is largely found in more humid regions, specifically:

The Pantanal floodplain ecosystem

Primarily within the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul

While both species can overlap slightly in distribution, X. pulcher tends to favor arid, dry shrubland environments, whereas X. mattogrossensis is more commonly associated with humid, seasonally flooded habitats.

Climate Comparison: Pantanal vs. Chaco

Feature

Pantanal (X. mattogrossensis)

Chaco (X. pulcher)

Geographic Location

Central-western Brazil (Mato Grosso & Mato Grosso do Sul)

Eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, northern Argentina

Climate Type

Tropical wet-and-dry

Subtropical to semi-arid

Annual Rainfall

39–75 inches (1,000–1,900 mm)

18–55 inches (450–1,400 mm)

Rainfall Pattern

Heavy rainfall Oct–Mar (wet season), dry Apr–Sep

Rain mainly in summer (Nov–Mar), long dry winters

Flooding

Extensive seasonal flooding (Oct–Mar)

Rare; soil retains little water, prone to drought

Temperature Range (Avg.)

73–77°F (23–25°C) year-round

Hot summers: up to 120°F (49°C), cold winters: down to 32°F (0°C)

Humidity

High during wet season (often >80%)

Low to moderate; dry air dominates most of the year

Vegetation

Seasonal wetlands, grasslands, gallery forest

Dry forests, thorn scrub, savanna

Ecological Stressors

Water fluctuation, flooding, humidity extremes

Heat extremes, dehydration, temperature swings

In short, X. mattogrossensis thrives in environments characterized by high humidity, seasonal moisture fluctuations, and flooding cues—conditions that reflect its native wetland habitat. Conversely, X. pulcher is adapted to hotter, drier climates with sharp seasonal temperature changes and consistently low humidity, aligning with its arid, Chacoan range. I believe these environmental differences play a significant role in the inconsistent success keepers report with “tricolor hognose” snakes. In my own experience, I unknowingly kept both species under identical conditions—same temperatures, same humidity—and witnessed stark differences: one group flourished, while the other failed to thrive, not realizing it was a different species. Assuming it was just a bad individual from an unethical seller.

"The Role of Diet in Long-Term Health and Reproduction"

Another critical factor affecting long-term success with these snakes is diet. In the wild, neither Xenodon pulcher nor Xenodon mattogrossensis regularly consume mammals. Due to the limited availability of safe feeder frogs, toads, and lizards in captivity—most of which are wild-caught and parasite-laden—keepers often rely on rodents as substitutes. While I’m not entirely opposed to feeding rodents, and have had some success with them, I believe they contribute significantly to health issues, particularly in breeding females.

In my experience, rats are especially problematic. Their high fat content often leads to digestive distress, including diarrhea or persistently loose stools—even if the snake is later transitioned back to mice. Mice are a better long-term option but still not ideal. I’ve observed that adult jumbo mice tend to cause the same digestive issues, likely due to their fat content. I’ve found better results feeding two smaller mice instead of a single jumbo one.

More recently, I’ve shifted to feeding whole chicks and quail to snakes large enough to consume them, with far greater success. Additionally, I’ve experimented with making “sausages” composed of frog legs (intended for human consumption, and thus safer than wild-caught amphibians) and whole chicks. This combination offers a more natural nutrient profile—frog legs mimicking part of their wild diet, and chicks providing necessary macro- and micronutrients. Reptilinks are another good option, though they can be cost-prohibitive when raising hundreds of tricolor hognose snakes.

While online sources often state a lifespan of 6–8 years, I have yet to meet anyone with a female that has bred consistently for more than three seasons. I did once encounter an 8-year-old female at a reptile show—massive in size and reportedly fed only chicks. The owner never bred her, which may explain her longevity.

Feeding during breeding cycles is a delicate balancing act. Too much food can be harmful; too little is equally problematic. Weekly feedings, in my opinion, are insufficient for cycling females, particularly after egg-laying. In my experience, females lay clutches roughly every 45 days once they begin cycling—similar to leopard geckos. A female may lay 3–8 clutches per season, with variability in clutch size (anywhere from 4 to 16 eggs, even from the same female in the same year).

Interestingly, tricolor hognose snakes expend less energy per clutch than other species, allowing them to lay more frequently. However, the overall toll on the female remains significant. After laying, she must rapidly replenish calories in preparation for the next cycle. Since ovulation occurs 10–14 days before laying, there’s roughly a 30-day window to restore her body condition. Failing to do so can result in reproductive complications. I’ve found that feeding every 3–4 days, offering two small mice per feeding with the occasional quail, yields the best results.

It’s also worth noting that tricolor hognose snakes often continue eating even while gravid. Some may refuse meals, but most do not—I’ve had females eat the day before, or even the morning of, egg laying. Large meals during this time increase the risk of egg binding.

Some breeders brumate their females after the third clutch to halt cycling, but I’ve hesitated to do so given how physically depleted the females are after multiple clutches. I've also tried avoiding male introductions to prevent repeated egg-laying, but this only led to multiple infertile clutches and, ironically, more egg binding issues.

In conclusion, I believe diet plays a pivotal role in the long-term health and longevity of tricolor hognose snakes. Amphibians are closest to their natural diet but can be challenging to source safely. Poultry offers the next best alternative, followed by mice. I strongly advise against feeding rats, as their fat content poses too many health risks for these species.

Reproductive Strain and Egg-Binding in Tricolor Hognose Snakes

Tricolor hognose snakes (Xenodon pulcher and X. mattogrossensis) exhibit remarkably high reproductive output, frequently laying between three to eight clutches per season, with individual clutches ranging from four to sixteen eggs. It is not uncommon for a single female to produce over 75 eggs in a single year. In my experience, females can reach sexual maturity as early as 11 months of age. However, this high reproductive capacity is accompanied by significant complications—chief among them, egg binding (dystocia), which I estimate occurs in approximately 20% of breeding females.

Due to the delicate, thin-shelled nature of their eggs, it is not unusual for eggs to collapse or become lodged within the oviduct. Large food items offered during gravidity appear to increase susceptibility to egg binding. In many of these cases, I have successfully used oxytocin to stimulate egg passage—even in situations where it may not typically be advised. In one instance, a male inadvertently remained in the enclosure with a gravid female. During oviposition, he bred her, which interrupted the laying process and ultimately resulted in fatal egg binding.

Another concerning pattern I’ve observed is the development of spinal deformities in females after laying multiple clutches—typically four or more. These "broken back"-like conditions occur without external trauma and exclusively affect females. Remarkably, many continue to eat, breed, and lay eggs despite the condition. I have also witnessed cases in which a female retained an egg from a prior clutch while simultaneously ovipositing a new one, indicating functional but staggered use of the oviducts.

While these outcomes may sound extreme, they underscore the biological strategy of these snakes, which appear to prioritize quantity over quality in reproduction. For keepers managing tricolor hognose snakes at scale, such complications may be an unfortunate but expected reality of the species’ intense reproductive cycle.

Incubation Techniques and Hatchling Rearing in Tricolor Hognose Snakes

One of the most misunderstood aspects of keeping tricolor hognose snakes is the incubation of their eggs. Many online care guides recommend incubation temperatures between 82–84°F. While I initially followed this advice and successfully hatched eggs within 60–65 days, I frequently encountered deformities among the hatchlings. Upon consulting with another experienced breeder, I was advised never to incubate above 80°F, based on his long-term experience with the species. Since adopting this approach, I have yet to produce a kinked or visibly deformed hatchling.

My preferred incubation temperature is 79°F, which consistently yields healthy offspring with an incubation period of approximately 80–100 days. I have also experimented with lower incubation temperatures—down to 70°F—with the aim of producing larger, potentially hardier offspring. While this did extend the incubation period to about 125 days, I did not observe significant health benefits to justify the increased duration. It’s worth noting that variation in incubation duration may also correlate with hybridization in captive populations, as other keepers report drastically different incubation periods for what is presumed to be the same species.

For substrate, I use vermiculite mixed with water in a sealed plastic container with a small pinhole for ventilation. While both perlite and vermiculite perform adequately, I personally prefer vermiculite due to its texture and moisture retention properties.

Once hatchlings emerge, I wait until they complete their post-hatch shed before offering food. It’s common for neonates to initially refuse live or frozen-thawed pinky mice. However, scenting the pinkies can significantly improve feeding response. I’ve tried various scenting agents—including frog legs, Vienna sausage water, and tuna—but have found the most reliable success using chicken liver juice. I soak the pinky in the juice, place it in a deli cup with the hatchling (without substrate), and often see immediate interest. This method has dramatically reduced the need for force-feeding, which I once had to do with nearly half of my hatchlings. Now, it's a rare necessity.

Once feeding begins, hatchlings typically continue eating without issue. The first few meals are the most critical. I’ve also spoken with other breeders who use small pieces of salmon as an initial food source, and some even keep large numbers of hatchlings (50–100) communally, similar to baby garter snake husbandry. While I cannot personally speak to the long-term success or drawbacks of communal rearing, the practice is intriguing and may warrant further exploration.

Final Thoughts on Breeding Tricolor Hognose Snakes

While this article may come across as cautionary, it’s not meant to discourage anyone from working with tricolor hognose snakes—only to present the realities of breeding this unique species. Yes, they are highly prolific and, at present, tend to have shorter reproductive lifespans for breeding females. But the key word is “for now.” These snakes are visually stunning, with vibrant coloration and a distinctive body shape, making them an incredibly fun and rewarding species to keep.

In fact, I believe they’re an ideal alternative to Western hognose snakes for families with young children. Their shorter lifespans, while often seen as a downside, can be a benefit for parents who don’t want to inherit a long-term pet once their child moves away to college.

This article isn’t a care guide—it’s an honest account of the challenges I’ve encountered, particularly regarding the reproductive demands placed on females. It’s not meant to dissuade anyone from keeping these snakes, but rather to share real-world experiences that can help others avoid the same pitfalls. For a more comprehensive care guide, including breeding instructions, I’ve published a detailed care sheet on my website: thebreedinglab.com.

The most important lessons I’ve learned through years of breeding this species are:

Know your species: Whether you’re working with X. pulcher, X. mattogrossensis, or a hybrid, accurate identification is critical.

Monitor your females closely: Keep them well-hydrated and well-fed throughout the breeding season.

Dehydration is common and can come on quickly: Even a female that drinks regularly can unexpectedly stop, so vigilance is key.

Do not cohabitate males and females during the cycling phase: A male introduced too early can stress a female, especially close to laying.

Substrate matters: I’ve found cypress mulch to be ideal. It resists mold when wet and performs well dry.

Incubate properly: Keep incubation temperatures below 80°F for healthier, well-formed offspring.

Above all, enjoy the process of breeding this fascinating species. There’s still much to learn, and by sharing observations and mistakes, we can all improve our success and care standards for tricolor hognose snakes.